Updated by Faith Barbara N Ruhinda at 1454 EAT on Thursday 2026

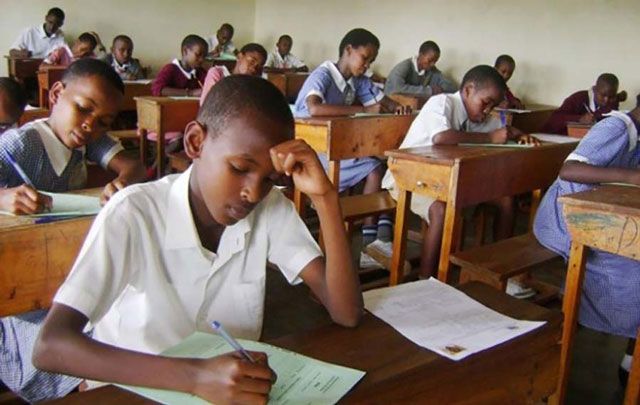

On Friday afternoon, as results from the Primary Leaving Examination (PLE) began circulating across Uganda, familiar rituals unfolded. Parents clustered around school noticeboards. Teachers scanned lists for recognisable names. In villages and city schools alike, the results marked the close of one chapter and the anxious beginning of another.

Yet beneath the celebrations and disappointments, the 2025 PLE results reveal a deeper and more complex story about the direction of Uganda’s education system—and the challenges it continues to face.

This year, a record 817,883 pupils sat the examination, the highest number ever recorded. The figure represents a 2.6 percent increase from last year and underscores the steady expansion of access to primary education, driven largely by the Universal Primary Education (UPE) programme.

Nearly two in three candidates—63.8 percent—were beneficiaries of the Universal Primary Education (UPE) programme, underscoring the extent to which public schools continue to shoulder Uganda’s education ambitions. Girls again made up the majority of candidates.

More than half of those who sat the examination—52.4 percent—were female, extending a trend that has persisted for several years. On the surface, the figures suggest steady progress toward gender parity. A closer look, however, reveals a more complicated picture.

While growing numbers of children are reaching the final year of primary school, relatively few are excelling across the curriculum.

Fewer than one in five pupils demonstrated high-level proficiency in all four tested subjects—English, Mathematics, Science, and Social Studies with Religious Education.

Instead, the majority of candidates—around two-thirds—fell into the “medium ability” category. In practical terms, most pupils demonstrated basic understanding but struggled with deeper reasoning, problem-solving, and applying what they had learned beyond the classroom.

The pattern points to an education system that has made gains in expanding access, but continues to struggle to translate attendance into strong learning outcomes.

Performance varied sharply by subject. English emerged as the strongest area, with 18.5 percent of candidates reaching the highest performance band—a notable improvement from 2024. The result suggests gains in reading and language instruction, an encouraging development in a system where English underpins learning across the curriculum.

Social Studies, however, presented a contrasting picture. The subject recorded the steepest decline, largely because pupils struggled with questions requiring the application of knowledge to real-life contexts, including civic rights, climate issues, and national heritage.

According to the Uganda National Examinations Board (UNEB), the results reflect a slow and uneven transition toward competency-based learning, which prioritises practical understanding over rote memorisation. In many classrooms—particularly outside the sciences—teaching methods have yet to fully make that shift.

Despite girls accounting for the majority of candidates, boys outperformed girls in most subjects except English. Among top performers in Divisions 1 and 2, 61.08 percent were boys, compared with 58.04 percent girls.

Boys also posted a marginally lower failure rate, a difference that remains small but consistent over time. Analysts say the gap reflects a range of structural pressures, including heavier domestic workloads for girls, early social expectations, and limited support for girls in subjects such as mathematics and science.

The findings have reignited calls for gender-responsive teaching approaches, particularly in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM), aimed at ensuring that gains in girls’ enrolment are matched by comparable academic performance.

One of the most striking—and least discussed—stories in this year’s results is who is being included. The number of Special Needs Education (SNE) candidates rose by 9.3 percent to 3,636 pupils.

Nearly half of them—48.4 percent—achieved Division 2, a strong outcome given the limited resources and specialised support many face. There were also quiet victories behind prison walls. Inmates from Luzira and Mbarara prisons recorded passes in Divisions 1 and 2, reinforcing the view that education can be rehabilitative even in the most restrictive environments.

While small in scale, these gains signal an education system that is gradually broadening its definition of who deserves access to learning—and the chance to succeed.

Where Learning Breaks Down

The Uganda National Examinations Board’s (UNEB) analysis highlights a recurring weakness: the application of knowledge. Pupils struggled with practical mathematics, such as percentages, interpreting written texts, and applying basic scientific concepts.

Social Studies questions that linked classroom learning to everyday civic life proved particularly challenging. The message is clear: too much learning remains theoretical, and too little is anchored in real-world problem-solving.

The implications extend well beyond primary school, shaping how learners cope with secondary education, vocational training, and eventually the workplace.

The results also exposed persistent challenges around examination malpractice. UNEB reported cases of bribery, coercion of invigilators, and increasingly sophisticated forms of cheating. As a result, results from Kampala, Kisoro, and Mukono were withheld pending investigations.

At the same time, districts such as Kyenjojo and Kabarole were commended for reforms and improved compliance—evidence that malpractice is not inevitable, but often reflects the strength of local leadership and enforcement.

The tension is familiar: expanding access while safeguarding credibility. If public trust in examinations erodes, certificates lose their value—and so does education’s promise as a pathway to social mobility.

A System at a Crossroads

Taken together, the 2025 PLE results point to a system in transition. Uganda has made measurable progress in access, inclusion, and gender parity. Yet learning outcomes remain uneven, and the shift toward competency-based education is still incomplete.

The challenge now is no longer simply enrolling more children, but ensuring they leave primary school with usable skills—the ability to think critically, solve problems, and participate meaningfully in society.

As Uganda looks ahead, the lesson from this year’s examinations is clear: expansion has opened the door. What happens next will depend on whether teaching practices, curriculum reform, and accountability are strong enough to walk through it.

Source: Observer

Invest or Donate towards HICGI New Agency Global Media Establishment – Watch video here

Email: editorial@hicginewsagency.com TalkBusiness@hicginewsagency.com WhatsApp +256713137566

Follow us on all social media, type “HICGI News Agency” .